“It is a bit far,” Prossy replied. We knew from working with the palliative care (PC) team over the past 10 years in rural Uganda that for Prossy to say “a bit far” meant at least an hour of being tossed around the back of the van as we drove over the deeply rutted dirt roads made particularly slow going during the current unexpected rainy season. Randi, Ben and Nav (two doctors from New York Presbyterian Hospital Cornell Palliative Care Division who we brought along on this Uganda trip) and I set off to see a woman about whom we knew no specifics, but had heard was suffering from an unknown illness that Prossy had been told about from someone who knew someone who heard from someone in a neighboring district; that’s how the referral network works out there.

An hour and a half later, shaken and buffeted by the van’s lack of shock absorbers or cushioned seats, we arrived at a village, not more than a kilometer from the shores of the Ugandan Nile River, yes, the same one that’s in Egypt, to find a woman in distress with a severely swollen belly filled with gallons of fluid and a massively enlarged spleen, a very unusual finding. The four US doctors stood baffled after examining her as to what was the underlying cause of her condition, not having the tools we were used to having in a US medical center (blood tests, scans, etc.) to make a definitive diagnosis. So we set to task at hand: Relieve her suffering.

As soon as she was more comfortable, a broad smile on her face, a villager came by to tell us of another person a little further down the road with similar complaints. Off we went to meet him under a mango tree. No sooner had we finished his examination when a young woman with a small baby strapped to her back came running across the fields, breathless, dragging her 6-year-old son who was not well, begging our team to see him. Word travels fast when we arrive in a village.

We originally started Palliative Care for Uganda, Inc (PCFU) to build self-sustainable programs to reduce suffering in people with chronic or life-limiting illnesses. While we continue to honor our original mission to support a team of palliative care nurses and nursing assistants to travel to rural villages in Uganda to provide palliative care and social support to those in need, we have more recently directed our efforts towards palliative care education for local practitioners, community health workers, and patients in effort to raise awareness of palliative care and improve access to alleviation of suffering, whether alongside treatment of the underlying illness or too often, when no treatment of the causative disease is possible.

This past year our organization (PCFU) has gone through what we can only describe as a gratifying explosion of work. As a result of all that we have learned over ten years about the overwhelming palliative care needs of people in rural Uganda, and through the partnerships we have nurtured over the years, we have been able to broaden our reach not only through Uganda, but also to other countries across the continent of Africa.

Here are some of the active projects going on this past year:

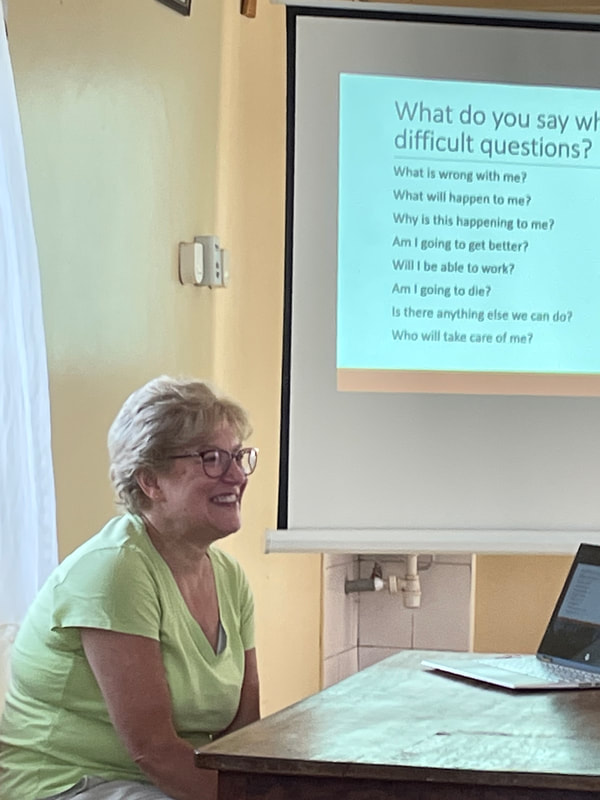

- Further development and implementation of a PCFU developed multi-modular video-based curriculum which we have created to educate healthcare workers about communication in palliative care. Through a partnership with The Institute of Hospice and Palliative Care in Africa it is being used at the university level to train nurses and doctors in principles of palliative care communication focusing on rural settings, something that, to our knowledge, has not been addressed before. Additional modules are in the planning stages.

- A series of webinars on grief and bereavement has been developed by Randi and her palliative care social work colleagues on understanding and managing grief and bereavement. Collaborating with the African Palliative Care Association, each of these webinars have been attended by as many as 150 on-line participants from 16 countries, bringing new ideas and approaches to areas with limited resources where such information is not readily available. More sessions are planned for the coming year.

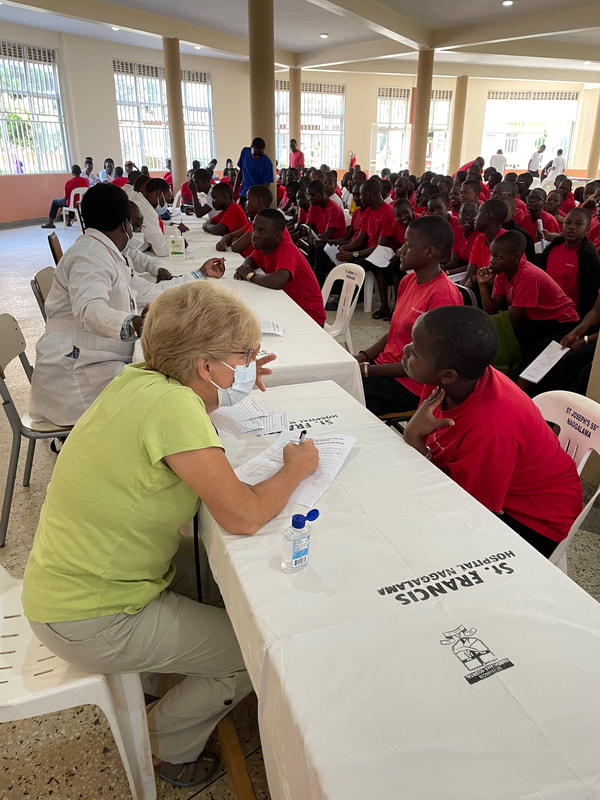

- Statistics show that close to 90% of palliative care needs are not met in many lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in Africa. PCFU conducted in-person educational programs at rural hospitals and with village health workers to raise awareness of what palliative care is, what it can do for their communities, and how it can be accessed. Presenting to over 200 people this past year, the Palliative Care Outreach Team has seen a 300% increase in referrals. Consequently, PCFU is now paying to educate and support additional nurses in specialty palliative care training to cover the increased needs in the villages.

- Last year we visited a young man with advanced cancer who was suffering in pain. We treated his pain, but when we explored how much he and his father understood about his cancer and its treatment, they presented a booklet they received from the Uganda Cancer Institute at their first visit called, “Coping with Cancer, A Booklet for Cancer Patients.” When the boy was diagnosed, no explanation of his disease was given except handing the father the book. “But we can’t read '', he explained to us. Because of this visit, and many similar encounters by our team in the rural villages, this year PCFU engaged with US- and African-based filmmakers to begin developing a series of short videos in local languages explaining cancer, its treatment, the side effects of treatments and how these symptoms can be managed. Last month we presented the first completed video to the heads of the Uganda Cancer Institute and the African Palliative Care Association. They loved it and we are now implementing a study with the Uganda Cancer Institute to study the impact these videos have on patients' experiences. The African Palliative Care Association has plans to distribute it to many countries, but this will require dubbing in several languages. More topics are planned for future videos.

- Every year we support doctors, doctors-in-training, nurses, and social workers from the US to see patients, develop research projects, give educational talks, and to learn for themselves about palliative care in LMIC’s. We also work with doctors and nurses not only from Uganda, but also from around the world, on the delivery of palliative care in rural areas. As we have heard before, on this past trip one of the four doctors who joined us this year told us, “This experience changed me both as a doctor and as a person.” We plan to continue to support bringing doctors, nurses, and social workers to Africa in the future. We are also hoping to bring healthcare workers from Africa to the US to see how palliative care works here.

Young Benjamin was standing next to his mother, his belly protruding like the adults we had just seen. Prossy translated. His mother said he hadn’t been able to play like other children in the village for at least the last two years. After a brief examination, it was clear that he had findings like the other two adults had. But first thing first, a lollipop for Benjamin that triggered a big smile and a swarm of other village children. So, we handed out more lollipops and balloons and soon noticed several of the children also had very distended bellies and large spleens. Perhaps this didn’t fall in the conventional definition of palliative care, but suffering is suffering so we knew we had to help.

We arranged to have a van pick up Benjamin, his mother and baby sister the next day and drive the hour and half to our base hospital to be hospitalized, see some specialists from Kampala, and get tests done, limited as they are compared to what is available in the US. We also started some treatments pending test results. We covered the costs for all of this, none of which was available to them in their village. We reached out to doctors back in the US for their opinions on this strange ailment affecting this village. As of the writing of this letter, results are still pending, the mystery unsolved, but we hope to help Benjamin and consequently his village.

Ten years ago, we started PCFU to help reduce suffering in a small corner of the world. We’ve grown. The organization is no longer a “mom and pop” organization, but an internationally recognized NGO with a mission to expand the reach of palliative care through education and resources on a continent-wide basis. Prossy and her team have taken care of over 900 patients in distress over the years, all at no cost to them. PCFU has no income other than philanthropy.

But as far as we’ve come, and as big as we’re dreaming, we still come back to the realization that even helping one person at a time, like young Benjamin, makes a big difference.

Howard and Randi

https://www.PCFUganda.org

RSS Feed

RSS Feed